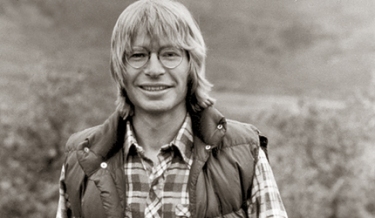

Currently, I’m having an issue with John Denver. At night, almost every night, his country hymns are the ones that lull my 7- and 4-year-olds to sleep.

I realize that in the grand scheme of things, the musical bedtime selections of our kids is not a big deal. And I acknowledge that overall, our kids’ tastes in music are quite varied. Like in the car, where they clamor for ’90s French rapper MC Solaar. Or in the kitchen, where they hang on for dear life to keep up with the rollercoaster that is Michael Jackson’s Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’. U2, Stevie Wonder, The Who, they dig all that.

But when you’re a mother of color trying to instill some sense of black culture in your kids — and the shiny meadows and shinier blonde mops all around you make you feel you’re already living a John Denver song — hearing those opening twangs about the Shenandoah River night after night after night can feel like a losing battle. I’m not sure how the CD, which belongs to my husband, first got into the rotation. But at bedtime, as their eyelids flutter and finally sink into sleep, there is only one voice Sky and Rose want to hear: the voice that sings Rocky Mountain High, Sunshine on My Shoulder and of course, the top grosser of all Denver’s hits, the ballad that gets mentioned with John Lennon’s Imagine and Aretha Franklin’s Respect as one of the most influential songs of the 20th century: Take Me Home, Country Roads. Attempts to slip in the occasional Erykah Badu or Harry Belafonte are futile.

“I like how his voice sounds singing with the music,” Sky explained the other night. “It sounds, you know, nice.” And part of me can’t argue with that four-star review — especially since I made a stink to Brian about the last CD that was in heavy rotation, Led Zeppelin II (remastered). I’m sure Sky and Rose have no idea what Robert Plant is talking about, but there’s something weird about peeking in on children bathed in the glow of a Hello Kitty lamp and hearing “Squeeze me baby/ ‘Til the juice runs down my leg” waft through the crack in the door.

Now, some have called Denver’s songs soaring melodies of hope. I would call them syrupy odes to romantic love and an idyllic notion of America that doesn’t really exist. I would not be alone in that assessment. In 2007, in the midst of an apparently heated battle over whether to declare Rocky Mountain High the state song of Colorado, a Denver Post columnist opined, “Rocky Mountain High deserves its place in Colorado . . . in Muzak form on supermarket speakers or during a marathon Time Life infomercial hosted by Air Supply.” Of course with music, it’s all relative. If Ray Charles and legendary ska band The Maytals saw fit to record covers of Take Me Home, there’s gotta be something to it that I’m missing.

And as I write this, I’m actually recalling another heated debate that took place right around 2007, in a cell phone conversation between Brian and me. I’ll attribute some of the things I said, and the conviction with which I said them, to the hormones coursing through my body during my second pregnancy. But I distinctly remember screaming about the importance of our kids understanding the revolutionary sound of A Tribe Called Quest. And I remember Brian saying something about hip-hop consisting of a lot of noise and only a very little bit of actual music.

The other day, as I heard Denver’s relentless major chords drift once again through the hall, I decided to try an experiment. I started Googling “John Denver” and “African-American,” just to see if there was any possible intersection of Denver and black culture other than in this house.

It didn’t take me long to find it.

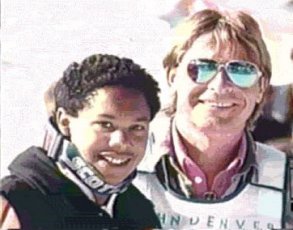

In the 1970s, after Denver married first wife Annie Martell, the couple had trouble conceiving. They adopted a son, Zachary John, and later a daughter, Anna Kate, who Denver would later say were “meant to be theirs.” The little boy who inspired Denver’s Zachary and Jennifer and A Baby Just Like You (which he wrote for Frank Sinatra), was black. If the Internet is to be believed, he is now in his 30s, happily married, and still lives in Colorado.

In an interview he gave to People in 1979, Denver talked about his family. He made no mention of race, but he made his feelings about fatherhood very clear. “I’ll tell you the best thing about me. I’m some guy’s dad; I’m some little gal’s dad. When I die, Zachary John and Anna Kate’s father, boy, that’s enough for me to be remembered by. That’s more than enough.”

Well I’ll be damned. There’s an idyllic notion of America, and I want to sing along.